It was very difficult to define what would be the first experience that should open this series “Colors of Japan”. There are so many images, feelings, learning, and inspirations brought by my memories of the trip to Japan! This trip was the result of the prize that I received for the textile work “Each Step” in 2016. The whole story you can find in this other post blog in Portuguese. I hope to translate it into English soon.

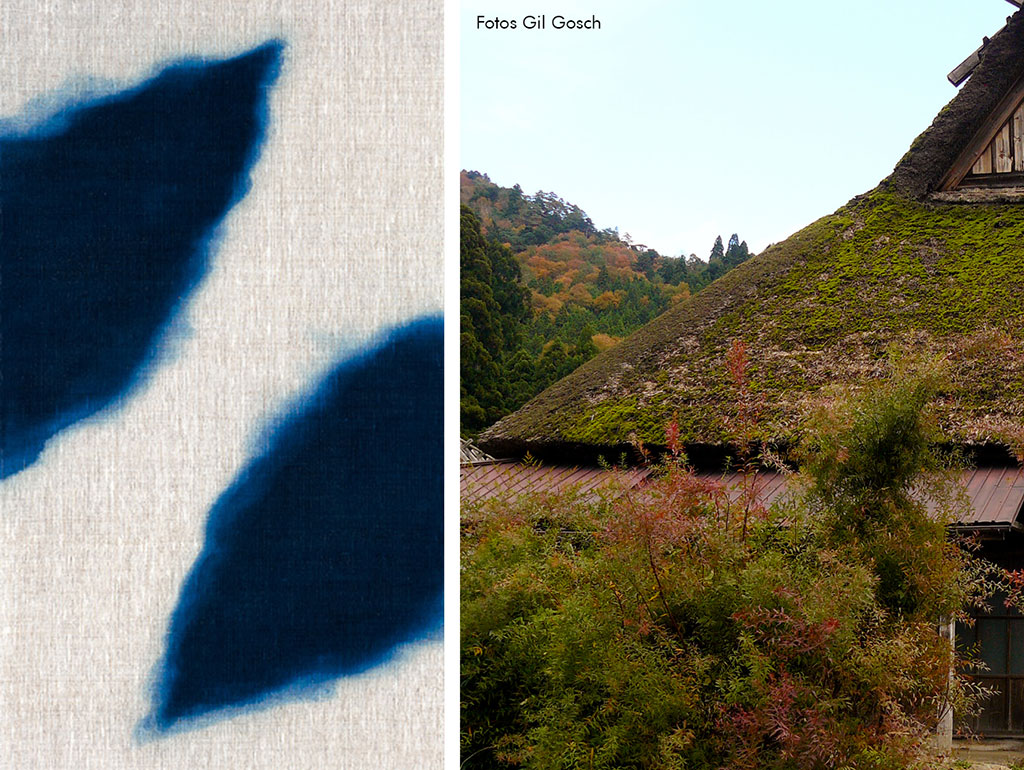

In Japan, in the fall of 2017, I discovered a world that preserves and gives great value to master craftsmen, who keep the techniques and secrets of natural dyeing and weaving. At the same time that they preserve the Japanese traditions, they develop in their work very contemporary aesthetic and ethical questions. I could see with my own eyes the ceaseless dialogue, on every corner, between the new and the tradition.

Perhaps my visit to the artist Hiroyuki Shindo was the pinnacle of that perception. Contemporary textile artist Hiroyuki Shindo was born in 1941 in Tokyo. He lives in the Miyama region, in a village in the mountains, 60 kilometres north of Kyoto, where he has had his studio since 1981. In 2005 he opened The Little Indigo Museum, which exhibits indigo-dyed pieces. Shindo sensei dedicated his life to preserving a tradition as Japanese as the dyeing of blue with indigo or, as the Japanese call it: the Aizome. I had the great privilege of knowing a tiny part of the blue universe and in this post, I try to share this precious with you.

A remote village at the foot of the mountains

Miyama is one of those unique places in the world. Soft rice fields lead us to the thatched roofs, some marked by the time, some brand new. These few houses mimic the landscape. It seems that we are walking inside a tale of rural Japan, in a very remote time. Above the roofs we see the slender pines that rise in the mountains, complementing the fall colours.

This was the place chosen by Hiroyuki Shindo to fix his blue art. And it was my interest in Japanese indigo blue that led me to meet Shindo sensei, his work, and Miyama. I dare say it was pure beginner’s luck.

And for the more curious and travellers, a little more information. Miyama is a rural area that is made up of multiple small villages and hamlets scattered along its narrow, winding valleys. The main attraction among them is the northern village Kayabuki no Sato Kita, which means Village (Sato) of thatched roof (Kayabuki) of North (Kita). According to the Japan-Guide website, this type of construction exists throughout Japan and is quite common in these surroundings. About 40 residences in this style exist in Kita. Most of them are a dwelling and, eventually, the workspace of the residents. This represents the largest percentage of kayabuki roofed houses in all of Japan. In 1994, the village was listed as a historic heritage site. Unfortunately, not all houses have thatched roofs. Its maintenance is very difficult and costly. All the straw needs to be replaced from time to time, when it is covered with green moss.

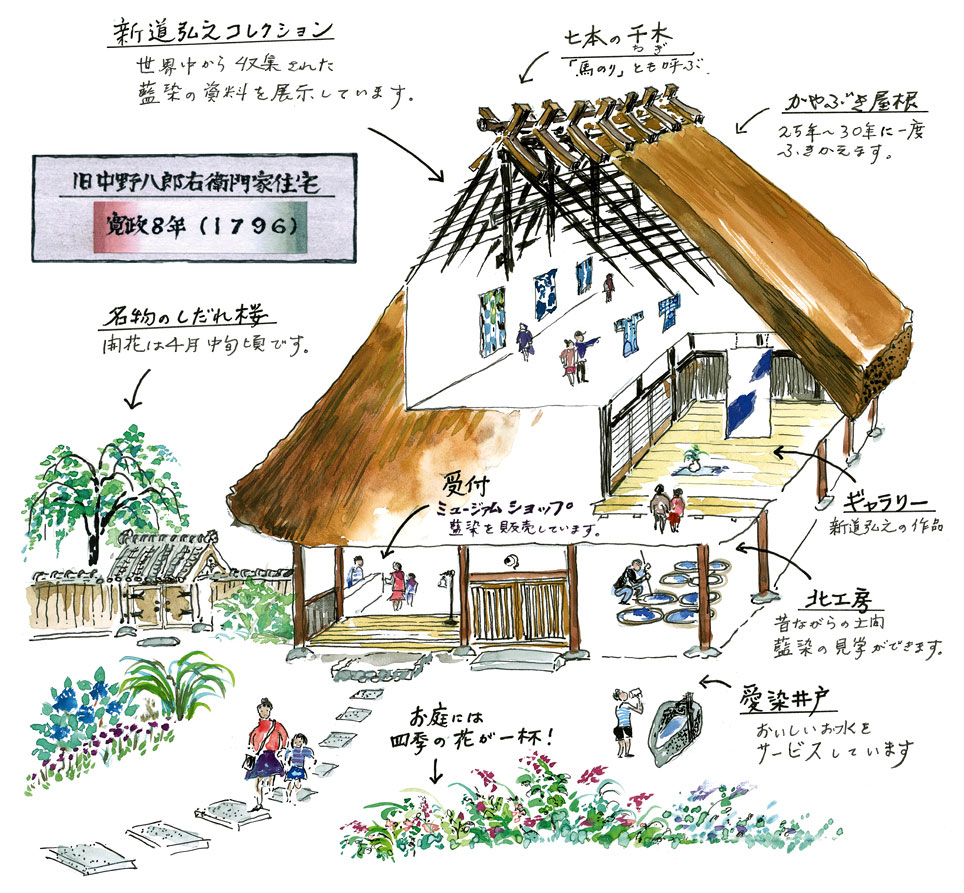

Hiroyuki Shindo’s house is the largest and oldest dwelling in the village. It was built over 200 years ago by a carpenter from the Wakasa district during the Edo period. The seven pairs of chestnut logs crossed at the top of the roof, attest to the fact that the house formerly belonged to a prominent elder of the village. This information is based on the data from the site www.shindo-shindigo.com as well as this drawing below, even with the Japanese subtitles, reveals a very good view of the house:

On the third floor, in a kind of attic, runs The Little Indigo Museum. On the first floor, we see the tokonoma, a sacred space that the Japanese usually have in their homes to contemplate the beautiful and impermanent things. And on the ground floor, we see the reception and the studio of Shindo sensei, where he works in the dyeing of indigo blue. Let’s visit him?

An entire life dedicated to the blue

“Indigo is a plant that has been used to making dyeing for thousands of years. Traces of that had been found around mummies at Egyptian tombs. An old artisan once said to me: ‘I am the last of fourteen generations of indigo dyers’. It´s sad to me to realize that such a wonderful technique would disappear in Japan. The more I learn about indigo, the more fascinated I became.” (Hiroyuki Shindo in the documentary Magicians Textiles)

Entering Shindo sensei’s studio is like going back in time. It is like entering the laboratory of an alchemist who keeps buried the secrets of his transmutation art. Turn green leaves into blue dye. The floor is of beaten earth, the wooden walls, many gadgets scattered here and there. The characteristic smell of indigo hangs in the air. The vats filled with the liquid that dyes blue are buried. But not to hide a secret, but to protect the precious tincture of the harsh Japanese winter. This is the traditional way of dyeing with indigo that Hiroyuki Shindo preserves and shares, teaching.

Dyeing with indigo is not easy. It is a long fermentation process that begins with the production of sukumo, a fermented compound made from the dried leaves of the Persicaria tinctoria plant. The tanks full of blue dye that we see in the photo are the result of a second fermentation where the sukumo is mixed with sake, rice bran, lime, and ash water, this last ingredient probably similar to the Brazilian decoada, traditionally used here in Brazil. The traditional aizome process uses only natural ingredients and no chemical substance. When the fermentation is successful, a blue foam is formed on the surface of the liquid called ai-no-Hana or indigo flower as we see in the photo. The indigo vat is similar to a yogurt culture – it is alive and must be fed. It is very sensitive and cold. If kept warm and happy, it will produce a range of blues starting with the sky-blue, passing through the turquoise, until reaching the deepest tones of a moonless night.

When the indigo vat is ready indigo dye, it´s time to dip the fabric. Shindo sensei, with his relaxed and affable way, made a demonstration of the dyeing in great English. He invented a system to facilitate the folding process of very long fabrics, probably used in kimonos. These folds create prints on the fabric and are part of the tradition of Shibori. Shibori (絞 り) is a set of techniques where we sew, fold, tie or fasten parts of the fabric to then dip it into the dye. The reserved parts of the fabric – tied or attached – will remain white forming the print.

Shindo sensei: “Indigo isn´t like today’s chemical dyes. The more you washing the more beautiful it becomes.”

The fabric is wrapped in the drum very carefully. The drum is raised by pulleys and ropes attached to the ceiling of the studio and dipped in the tincture of indigo. As soon as the fabric is removed from the dye we perceive a bluish-green color. In contact with the air, the magic happens: through oxidation, the green is transferred in blue, blue as the sky! The drum is taken to a tank, where it is unwound. Shindo sensei vigorously washes the fabric in running water. In his words: “Indigo isn´t like today chemical dyes. The more you washing the more beautiful it becomes.”

Since this rational process demands such sensitive perception that only a sort of ‘sixth sense’ or instinct can control it. We indigo dyers have no choice but to trust in the God of Indigo (Aizen Shin) who is enshrined in our workshops and to whom we pray for luck before starting any dyeing process.” (Hiroyuki Shindo)

The Little Indigo Museum

Hiroyuki Shindo’s passion for indigo blue was not contained, and he was beyond borders. In 2015, he created The Little Indigo Museum. Occupying the attic of your home, the museum is a very special place. With a blue soul, in this place, Shindo sensei materializes his passion for indigo, sharing it with all of us. In every detail of the collection, we can see his care and affection. Let’s listen to Hiroyuki Shindo himself talking about his creation:

“I first encountered indigo as a student at Kyoto City University of Fine Arts in the late 1960’s. The more I studied indigo, the more fascinated I became. Since then, my indigo dye works have been exhibited throughout Japan and abroad. Unlike other large museum collections, this one started when I was a poor art student exploring flea markets in search of traditional indigo textiles. Over the years, I’ve also discovered indigo textiles among discarded belongings, collected them during field trips, and have simply received pieces from people along the way. Indigo has a universal appeal and a history of being used in textiles as a mystical colour. It has even been found used as ancient Egyptian mummy wrappings. Today, the fascination with indigo continues among many cultures. This collection includes examples not only from Japan but also from Asia, Africa, Europe, and Central America. I hope you enjoy this representation of indigo dye culture from all over the world.” (shindo-shindigo.com website)

Some images of the treasures I saw there:

kabuki theatre Japanese kimono

Japaneses kimonos

Mexican textil

Work in blue

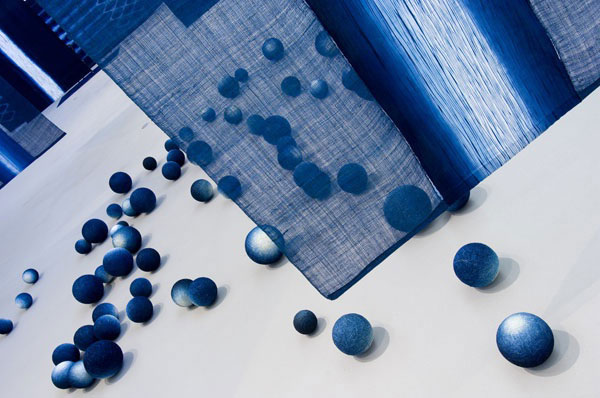

The work of Hiroyuki Shindo has a bewildering simplicity and lightness. All this freedom is solidly seated in the deep blue. And this blue can only be achieved by knowing deeply the ancient technique of aizome or indigo dyeing. Our contemporary world in direct dialogue with the Japanese tradition.

By creating my works using natural materials only, I wish to lead people to reconsider: what is nature? And: what is the Japanese tradition?” (Hiroyuki Shindo)

Hiroyuki Shindo’s work has been exhibited and is part of the permanent collections of some important museums around the world like the Museum of Art and Design, New York; the Cleveland Museum of Art; Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, Mexico City; The Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester; and the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

The film Textile Magicians by Cristobal Zanartu is a great 1997 documentary that follows the creative process of 5 textile artists in the forests near Kyoto. They are Masakazu Kobayashi, Chiyoko Tanaka, Jun Tomita, Naomi Kobayashi, and our Hiroyuki Shindo. Unfortunately, it has no translation in Portuguese, but through the beautiful images, we can intuit the search of each artist and follow the artistic process of Hiroyuki Shindo. And above all to feel the great inspiration of these artists that in the strength of the tradition of Japanese culture find their free flow artistic. And they return to us their love and respect for nature.

“Natural indigo does not damage the environment. I returned to the earth what it has given to me. It is a traditional Japanese value to live in harmony with nature and I hold this value close to my heart.” (Hiroyuki Shindo in the documentary Magicians Textiles)

Gasshô Shindo sensei! 🙏🙏🙏

Colours of Japan

This is the first post in the “Colors of Japan” series, a travel diary retelling my experience visiting Japanese artists who work with traditional techniques of natural dyeing and weaving. A way to reciprocate, thank you and share so many beautiful experiences that I learned there.

If you’d like to follow along with the blog, you are welcome to sign up to my mailing list. You will be the first to receive the new posts.

See you in the next chapter of the voyage!

Discover the products of the online store dyed by hand with leaves brought from Japan in harmony with Brazilian plants:

Credit

Photography and text revision by Gil Gosch, except the reproductions of the works.

[…] dyeing and weaving. I visited the Ars Shimura school of master artisan Fukumi Shimura in Kyoto; the Little Indigo Museum of textile artist Hiroyuki Shindo in Miyama, and the Japanese Botanical Garden of Dyeing Plants in […]

I’m constantly learning from your posts. illplaywithyou